Ribonukleotide

Ribonukleotide sind die Bausteine der Ribonukleinsäure (RNA). Zusammen mit den Desoxyribonukleotiden gehören sie zu den Nukleotiden. Ribonukleotide bestehen aus einem Nukleosid, in dem der Zucker D-Ribose mit einer der Nukleobasen – wie den Purin-Basen Adenin (A) und Guanin (G) oder den Pyrimidin-Basen Cytosin (C), Uracil (U) und selten Thymin (T) – verknüpft ist, sowie einem Phosphatrest.

Monophosphate

In der Lebensmittelindustrie werden Mischungen von Ribonukleotiden mit einer Phosphatgruppe (Nukleosidmonophosphate, NMP) als Geschmacksverstärker verwendet und als Calcium-5′-ribonucleotid (E 634), Dinatrium-5′-ribonucleotid (E 635) deklariert:

Adenosinmonophosphat

(AMP)Guanosinmonophosphat

(GMP)Cytidinmonophosphat

(CMP)- Uridinmonophosphat protoniert.svg

Uridinmonophosphat

(UMP)

Diphosphate

Die natürlichen Nukleosiddiphosphate (NDP) sind:

Adenosindiphosphat

(ADP)Guanosindiphosphat

(GDP)- Cytidindiphosphat protoniert.svg

Cytidindiphosphat

(CDP) - Uridindiphosphat protoniert.svg

Uridindiphosphat

(UDP)

Triphosphate

Die natürlichen Nukleosidtriphosphate (NTP) sind:

- Adenosintriphosphat protoniert.svg

Adenosintriphosphat

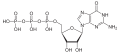

(ATP) Guanosintriphosphat

(GTP)- Cytidintriphosphat protoniert.svg

Cytidintriphosphat

(CTP) Uridintriphosphat

(UTP)

Vorkommen

Ribonuklotidmonophosphate in Lebensmitteln

| Lebensmittel tierischen Ursprungs |

IMP Massenanteil in % |

GMP Massenanteil in % |

AMP Massenanteil in % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rindfleisch | 0,070[1] | 0,004[1] | 0,008[1] |

| Schweinefleisch | 0,200[1] | 0,002[1] | 0,009[1] |

| Hühnerfleisch | 0,201[1] | 0,005[1] | 0,013[1] |

| Muttermilch | 0,0003[2] | unbekannt[2] | unbekannt[2] |

| Kalmar | unbekannt[1] | unbekannt[1] | 0,184[1] |

| Thunfisch | 0,286[1] | unbekannt[1] | 0,006[1] |

| Lachs | 0,154[2] | Spuren[2] | 0,006[2] |

| Kabeljau | 0,044[2] | unbekannt[2] | 0,023[2] |

| Makrele | 0,215[2] | Spuren[2] | 0,006[2] |

| Jakobsmuschel | unbekannt[1] | unbekannt[1] | 0,172[1] |

| Hummer | Spuren[2] | Spuren[2] | 0,082[2] |

| Garnele | 0,092[2] | Spuren[2] | 0,087[2] |

| Krabbe | 0,005[2] | 0,005[2] | 0,032[2] |

| Anchovi | 0,300[2] | 0,005[2] | unbekannt[2] |

| Sardine | 0,193[2] | unbekannt[2] | 0,006[2] |

| Seeigel | 0,002[2] | 0,002[2] | 0,010[2] |

| Lebensmittel pflanzlichen oder pilzigen Ursprungs |

IMP Massenanteil in % |

GMP Massenanteil in % |

AMP Massenanteil in % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tomate | unbekannt[1] | unbekannt[1] | 0,021[1] |

| Tomate, getrocknet | Spuren[2] | 0,010[2] | unbekannt[2] |

| Kartoffel, gekocht | Spuren[2] | 0,002[2] | 0,004[2] |

| Erbse | unbekannt[1] | unbekannt[1] | 0,002[1] |

| Spargel, grün | Spuren[2] | Spuren[2] | 0,004[2] |

| Nori | 0,009[2] | 0,005[2] | 0,052[2] |

| Shiitake, getrocknet | unbekannt[1] | 0,150[1] | unbekannt[1] |

| Steinpilz, getrocknet | unbekannt[1] | 0,010[1] | unbekannt[1] |

| Austernpilz, getrocknet | unbekannt[1] | 0,010[1] | unbekannt[1] |

| Morchel, getrocknet | unbekannt[1] | 0,040[1] | unbekannt[1] |

| Enoki | unbekannt[2] | 0,022[2] | unbekannt[2] |

Einzelnachweise

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj Shizuko Yamaguchi, Kumiko Ninomiya: Umami and Food Palatability. In: The Journal of Nutrition. 130, 2000, S. 921S–926S, doi:10.1093/jn/130.4.921S.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as Ole G. Mouritsen, Klavs Styrbæk: Umami. Columbia University Press, 2014, ISBN 978-0-231-16890-8. S. 226–231.

Literatur

- Jeremy M. Berg, John L. Tymoczko, Lubert Stryer: Biochemie, 6. Auflage, Spektrum Akademischer Verlag, Heidelberg 2007, ISBN 978-3-8274-1800-5.

- Donald Voet, Judith G. Voet: Biochemistry, 3. Auflage, John Wiley & Sons, New York 2004, ISBN 0-471-19350-X.

- Bruce Alberts, Alexander Johnson, Peter Walter, Julian Lewis, Martin Raff, Keith Roberts: Molecular Biology of the Cell, 5. Auflage, Taylor & Francis 2007, ISBN 978-0-81534106-2.