Benutzer:Er nun wieder/Doklam

Wenn du dies liest:

|

Wenn du diesen Artikel überarbeitest:

|

Vorlage:Use dmy dates Koordinaten fehlen! Hilf mit. Vorlage:Infobox landform

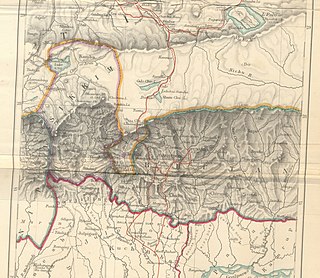

Doklam (in Standard Bhutanese), Zhoglam (in Standard Tibetan),[1] or Donglang (in Chinese),[2][3] is an area with a plateau and a valley, lying between China's Chumbi Valley to the north, Bhutan's Ha Valley to the east and India's Sikkim state to the west. It has been depicted as part of Bhutan in the Bhutanese maps since 1961, but it is also claimed by China. To date, the dispute has not been resolved despite several rounds of border negotiations between Bhutan and China.[4][5][6] The area is of strategic importance to all three countries.[7]

In June 2017 a military standoff occurred between China and India as China attempted to extend a road on the Doklam plateau southwards near the Doka La pass and Indian troops moved in to prevent the Chinese to no avail. India claimed to have acted on behalf of Bhutan, with which it has a 'special relationship'.[4][5]Vorlage:Sfnp Bhutan has formally objected to China's road construction in the disputed area.[8]

Geography

The Imperial Gazetteer of India, representing the 19th century British view of the territory, states that the Dongkya range that separates Sikkim from the Chumbi Valley bifurcates at Mount Gipmochi into two great spurs, one running south-west and the other running south-east. Between these two spurs runs the valley of the Dichul or Jaldhaka river.[9]

However, the Dongkya range that normally runs in the north–south direction gently curves to east–west at the southern end of the Chumbi Valley, running through the Batang La and Sinchela passes and sloping down to the plain. A second ridge to the south, called the Zompelri or Jampheri ridge, runs parallel to the first ridge, separated by the Doklam or Doka La valley in the middle. At the top of the valley, the two ridges are joined, forming a plateau. The highest points of the plateau are on its western shoulder, between Batang La and Mount Gipmochi, and the plateau slopes down towards the southeast. A stream flows down the Doklam valley collecting the run-off water from the plateau, and joins the Amo Chu river about 15 km to the southeast.

The 89 km2 area between the western shoulder of the plateau and the joining point of the Doklam stream with the Amo Chu river is called Doklam ('rocky path').Vorlage:Sfnp[lower-alpha 1]

India's Sikkim state lies to the west of the Dongkya range, the western shoulder of the Doklam plateau and the 'southwest spur' issuing from Mount Gipmochi. The Zompelri ridge separates Bhutan's Haa District (to the north) and the Samtse (to the south). Bhutan's claimed border runs along the northern ridge of the Doklam plateau until Sinchela and then moves down the valley to the Amo Chu river. China's claim of the border includes the entire Doklam area within the Chumbi Valley, ending at the Zompelri ridge on the south and the joining point of the Doklam river on the east.

Strategic significance

Scholar Susan Walcott counts China's Chumbi Valley, to the north of Doklam, and India's Siliguri Corridor, to the south of Doklam, among "strategic mountain chokepoints critical in global power competition".Vorlage:Sfnp John Garver has called the Chumbi Valley "the single most strategically important piece of real estate in the entire Himalayan region".Vorlage:Sfnp The Chumbi Valley intervenes between Sikkim and Bhutan south of the high Himalayas, pointing towards India's Siliguri Corridor like a "dagger". The latter is a narrow 24 kilometer-wide corridor between Nepal and Bangladesh in India's West Bengal state, which connects the central parts of India with the northeastern states including the contested state of Arunachal Pradesh. Often referred to as the "chicken's neck", the Siliguri Corridor represents a strategic vulnerability for India. It is also of key strategic significance to Bhutan, containing the main supply routes into the country.[12]

Historically, both Siliguri and Chumbi Valley were part of a highway of trade between India and Tibet. In the 19th century, the British Indian government sought to open up the route to British trade, leading to their suzerainty over Sikkim with its strategic Nathu La and Jelep La passes into the Chumbi Valley. Following the Anglo-Chinese treaty of 1890 and Younghusband expedition, the British established trading posts at Yatung and Lhasa, along with military detachments to protect them. These trade relations continued till 1959, when the Chinese government terminated them.[13] The Doklam area, however, had little role in these arrangements because the main trade routes were either through the Sikkim passes or through the interior of Bhutan entering the Chumbi Valley in the north near Phari. There is some fragmentary evidence of trade through the Amo Chu valley, but the valley is said to have been narrow with rocky faces with a torrential flow of the river, not conducive for a trade route.[14][15]

Indian intelligence officials state that China had been carrying out a steady military build-up in the Chumbi Valley, building many garrisons and converting the valley into a strong military base.Vorlage:Sfnp In 1967, border clashes occurred at Nathu La and Cho La passes, when the Chinese contested the Indian demarcations of the border on the Dongkya range. In the ensuing artillery fire, states scholar Taylor Fravel, many Chinese fortifications were destroyed as the Indians controlled the high ground.Vorlage:Sfnp In fact, the Chinese military is believed to be in a weak position in the Chumbi Valley because the Indian and Bhutanese forces control the heights surrounding the valley.[11][16]

The desire for heights is thought to bring China to the Doklam plateau.[17] Indian security experts mention three strategic benefits to China from a control of the Doklam plateau. First, it gives it a commanding view of the Chumbi valley itself. Second, it outflanks the Indian defences in Sikkim which are currently oriented northeast towards the Dongkya range. Third, it overlooks the strategic Siliguri Corridor to the south. A claim to the Mount Gipmochi and the Zompelri ridge would bring the Chinese to the very edge of the Himalayas, from where the slopes descend into the southern foothills of Bhutan and India. From here, the Chinese would be able to monitor the Indian troop movements in the plains or launch an attack on the vital Siliguri corridor in the event of a war. To New Delhi, this represents a "strategic redline".[4][11][18] Scholar Caroline Brassard states, "its strategic significance for the Indian military is obvious."[19]

History

The historical status of the Doklam plateau is uncertain.

According to the Sikkimese tradition, when the Kingdom of Sikkim was founded in 1642, it included all the areas surrounding the Doklam plateau: the Chumbi Valley to the north, the Haa Valley to the east as well as the Darjeeling and Kalimpong areas to the southwest. During the 18th century, Sikkim faced repeated raids from Bhutan and these areas often changed hands. After a Bhutanese attack in 1780, a settlement was reached, which resulted in the transfer of the Haa valley and the Kalimpong area to Bhutan. The Doklam plateau sandwiched between these regions is likely to have been part of these territories. The Chumbi Valley was still said to have been under the control of Sikkim at this point.Vorlage:SfnpVorlage:Sfnp

Historians doubt this narrative, Saul Mullard states that the early kingdom of Sikkim was very much limited to the western part of modern Sikkim. The eastern part was under the control of independent chiefs, who did face border conflicts with the Bhutanese, losing the Kalimpong area.Vorlage:Sfnp The possession of the Chumbi Valley by the Sikkimese is uncertain, but the Tibetans are known to have fended off Bhutanese incursions there.Vorlage:Sfnp

After the unification of Nepal under the Gorkhas in 1756, Nepal and Bhutan had coordinated their attacks on Sikkim. Bhutan was eliminated from the contest by an Anglo-Bhutanese treaty in 1774.[21] Tibet enforced a settlement between Sikkim and Nepal, which is said to have irked Nepal. Following this, by 1788, Nepal occupied all of the Sikkim areas to the west of the Teesta river as well as four provinces of Tibet.Vorlage:Sfnp Tibet eventually sought the help of China, resulting in the Sino-Nepalese War of 1792. This proved to be a decisive entry of China into the Himalayan politics. The victorious Chinese General ordered a land survey, in the process of which the Chumbi valley was declared as part of Tibet.Vorlage:Sfnp The Sikkimese resented the losses forced on them in the aftermath of the war.Vorlage:Sfnp

In the following decades, Sikkim established relations with the British East India Company and regained some of its lost territory after an Anglo-Nepalese War. However, the relations with the British remained rocky and the Sikkimese retained loyalties to Tibet. The British attempted to enforce their suzerainty via the Treaty of Tumlong in 1861. In 1890, they sought to exclude the Tibetans from Sikkim by establishing a treaty with the Chinese, who were presumed to be exercising suzerainty over Tibet. The Anglo-Chinese treaty recognised Sikkim as a British protectorate and defined the border between Sikkim and Tibet as the northern watershed of the Teesta River (on the Dongkya range), starting at "Mount Gipmochi". However, what was meant by "Mount Gipmochi" is unclear and no land surveys of the area had been done prior to the treaty. Some British travel maps from the 19th century (prior to official surveys) mark the Doklam plateau itself as the "Gipmochi Pk" and show its location adjacent to the Sinchela pass (on the northern ridge of the plateau).[20] In 1904, the British signed another treaty with Tibet, which confirmed the terms of the Anglo-Chinese treaty. The boundary established between Sikkim and Tibet in the treaty still survives today, according to scholar John Prescott.[22]

Bhutan became a protected state (though not a 'protectorate') of British India in 1910, an arrangement that was continued by independent India in 1949.[23] However, Bhutan retained its independence in all internal matters and its borders were not demarcated until 1961.[24] It is said that the Chinese cite maps from before 1912 to stake their claim over Doklam.[25]

Sino-Bhutanese border dispute at Doklam

Depictions of historical Chinese maps by the People's Republic of China show Sikkim and Bhutan as part of Tibet or China for a period of 1800 years, starting from the second century B.C., yet others note that these areas were not under Chinese control except for a short period in the 19th century[lower-alpha 2] From 1958, Chinese maps started showing large parts of Bhutanese territory as part of China.[26] In 1960, China issued a statement claiming that Bhutan, Sikkim and Ladakh were part of a unified family in Tibet and had always been subject to the "great motherland of China".[27]Vorlage:Sfnp[lower-alpha 3] Alarmed, Bhutan closed off its border with China and shut all trade and diplomatic contacts.[27] It also established formal defence arrangements with India.[26]

1960s

Starting August 1965, China and India traded accusations regarding intrusions into Doklam. China alleged that Indian troops were crossing into Doklam (which they called "Dognan") from Doka La, carrying out reconnaissance and intimidating Chinese herders. At first, the Indians paid no attention to the complaint. However, after several rounds of exchanges, on 30 September 1966, they forwarded a protest from the Bhutanese government which stated that Tibetan grazers were entering the pastures near the Doklam plateau accompanied by Chinese patrols. The letter asserted that the Doklam area was to the "south of the traditional boundary between Bhutan and the Tibet region" in the southern Chumbi area. On 3 October, the Government of Bhutan issued a press statement in which it said, "this area is traditionally part of Bhutan and no assertion has been made by the Government of the People's Republic of China disputing the traditional frontier which runs along recognizable natural features."[26][27][31][lower-alpha 4][lower-alpha 5]

In response, the Chinese government replied that Bhutan was a sovereign country and that China did not recognize any role for the Indian government in the matter. It also asserted that the Doklam area had "always been under Chinese jurisdiction", that the Chinese herdsmen had "grazed cattle there for generations" and that the Bhutanese herdsmen had to pay pasturage to the Chinese side to graze cattle there.[32][lower-alpha 6]

China later formally extended claims to 300 sq. miles of territory in northern Bhutan and areas north of Punakha, but apparently not in Doklam. Bhutan requested the Indian government to raise the matter with China. However, China rejected India's initiatives stating that the issue concerned China and Bhutan alone.[33][34] Indian commentators state that the Chinese troops withdrew after a month and that the fracas over Doklam brought Bhutan even closer to India, resulting in the appointment of 3,400 Indian defence personnel in Bhutan for training the Bhutanese Army.[26]

Border negotiations

Border negotiations between Bhutan and China began in 1972 with India's participation. However, China sought the exclusion of India due to its effect on Bhutan.[27] Bhutan commenced its own border negotiations with China in 1984. Prior to putting forward its claim line, it carried out its own surveys and produced maps that were approved by the National Assembly in 1989. Strategic expert Manoj Joshi states that the Bhutanese voluntarily shed territory in the process.Vorlage:Sfnp Other scholars noted a reduction of 8,606 km2 area in the official Bhutanese maps. The Kula Kangri mountain, touted as the tallest peak in Bhutan, has apparently been ceded to China.Vorlage:Sfnp Bhutan said that, through the course of border talks, it had reduced 1,128 km2 of disputed border areas to 269 km2 by 1999.[35] In 1996, the Chinese negotiators offered a "package deal" to Bhutan, offering to give up claims on 495 km2 in the central region in exchange for 269 km2 in the "northwest", i.e., adjacent to the Chumbi valley, including Doklam, Sinchulumpa, Dramana and Shakhatoe. These areas would offer strategic depth to Chinese defences and access to the strategic Siliguri Corridor of India. Bhutan turned down the offer, reportedly under India's pressure.[36][37]

Having turned down China's package deal, in 2000, Bhutanese government put forward its original claim line of 1989. The talks could make no progress afterwards. The government reported that, in 2004, China started building roads in the border areas, leading to repeated protests by the Bhutanese government based on the 1998 Peace and Tranquility Agreement.[38] According to a Bhutanese reporter, the most contested area has been the Doklam plateau.[39] Chinese built a road up the Sinchela pass (in undisputed territory) and then over the plateau (in disputed territory), leading up to the Doka La pass, until reaching within 68 metres to the Indian border post on the Sikkim border. Here, they constructed a turn-around facilitating vehicles to turn back. This road has been in existence at least since 2005.[4]Vorlage:Sfnp[40] In 2007, there were reports of the Chinese having destroyed unmanned Indian forward posts on the Doklam plateau.Vorlage:SfnpVorlage:Sfnp

Current position

China claims the Doklam area as Chinese territory based on the Anglo-Chinese Convention of 1890, negotiated between the British Empire in India and the Chinese royal mission.[41][42] The treaty states that representatives of Sikkim and Tibet were part of these negotiations, but records show that they were not present during the negotiations in Calcutta.[42][43] The territorial boundary between Sikkim and Tibet was delineated in the Article I of the treaty in the following manner: Vorlage:Quote Mochu is the Tibetan name for the Amo Chu river. Gipmochi is mentioned in the Article as being on the Bhutan border, but no further details regarding Bhutan were given. Bhutan was not a signatory to the Anglo-Chinese treaty.Vorlage:Sfnp

Bhutan's position was described in 2002: Vorlage:Quote In 2004, Bhutan's Secretary for International Borders reported the same claims to the National Assembly.[6]

The Diplomat has commented that the continuous mountain crest or watershed mentioned in the first sentence of the 1890 treaty appears to begin very near Batang La, on the northern ridge of the Doklam plateau, and that this suggests a contradiction between the first and second sentences of the above article of the treaty.[4] This Batang La location is depicted and claimed as the trijunction point by Bhutan and India.

According to scholar Srinath Raghavan, the watershed principle in the first sentence implies that the Batang La–Merug La–Sinchela ridge should be the China–Bhutan border because both Merug La, at Vorlage:Convert, and Sinchela, at Vorlage:Convert, are higher than Gipmochi at Vorlage:Convert.[44]

Bhutan and China border agreements 1988 and 1998

Bhutan and China have held 24 rounds of boundary talks since it began in 1984. The Royal Government of Bhutan claims that the present road construction on the Doklam Plateau amounts to unilateral change to a disputed boundary by China in violation of the 1988 and 1998 agreements between the two nations. The agreements also prohibit he use of force and encourage both parties to strictly adhere to use peaceful means. Vorlage:Quote

Notwithstanding the agreement, the PLA crossed into Bhutan in 1988 and took control of the Chumbi Valley near the Doklam plateau. There were reports of the PLA troops threatening the Bhutanese guards, declaring it to be Chinese soil, and seizing and occupying Bhutanese posts for extended periods.[27] Again, after 2000, numerous intrusions, grazing and road and infrastructure construction by the Chinese were reported as reported in the Bhutanese National Assembly.[38]

2017 Doklam standoff

Vorlage:OSM Location map In June 2017, Doka La became the site of a stand-off between the armed forces of India and China following an attempt by China to extend a road from Yadong further southward on the Doklam plateau. India does not have a claim on Doklam but it supports Bhutan's claim on the territory.[45] According to the Bhutanese government, China attempted to extend a road that previously terminated at Doka La towards the Bhutan Army camp at Zompelri two km to the south; that ridge, viewed as the border by China but as wholly within Bhutan by both Bhutan and India, extends eastward overlooking India's highly-strategic Siliguri corridor.[46]

On 18 June, Indian troops crossed into the territory in dispute between China and Bhutan in an attempt to prevent the road construction.[47]

India's entry into the dispute is explained by the extant relations between India and Bhutan. In a 1949 treaty, Bhutan agreed to let India guide its foreign policy and defence affairs, making it a protected state of India. In 2007, that treaty was superseded by a new friendship treaty that made it mandatory on Bhutan to take India's guidance on foreign policy, but providing it broader sovereignty in other matters such as arms imports.[48][49]

India charges that China has violated this 'peace agreement' by trying to construct roads in Doklam.[50]

India has criticised China for "crossing the border" and attempting to construct a road (allegedly done "illegally"), while China has criticised India for entering its "territory".[51]

On 29 June 2017, Bhutan protested the Chinese construction of a road in the disputed territory.[52] The Bhutanese border was put on high alert and border security was tightened as a result of the growing tensions.[53] On the same day, China released a map depicting Doklam as part of China, claiming, via the map, that all territory up to Gipmochi belonged to China by the 1890 Britain-China treaty.[54]

On 3 July 2017, China told India that former Indian prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru accepted the 1890 Britain-China treaty.[55] Contrary to Chinese claim, Nehru's 26 September 1959 letter to Zhou, cited by China, was a point-by-point refutation of the claims made by the latter on 8 September 1959. Nehru made it amply clear in his rebuttal that the 1890 treaty defined only the northern part of the Sikkim-Tibet border and not the tri-junction area.Vorlage:Citation needed

China claimed on 5 July 2017 that there was a "basic consensus" between China and Bhutan that Doklam belonged to China, and there was no dispute between the two countries.[56] The Bhutanese government in August 2017 denied that it had relinquished its claim to Doklam.[57]

In a 15-page statement released on 1 August 2017, the Foreign Ministry in Beijing accused India of using Bhutan as "a pretext" to interfere and impede the boundary talks between China and Bhutan. The report referred to India's "trespassing" into Doklam as a violation of the territorial sovereignty of China as well as a challenge to the sovereignty and independence of Bhutan.[58]

Chinese diplomat Wang Wengli claimed that Bhutan did not claim the territory, but this was unsubstantiated.[59]

Chinese position

The Chinese government maintains that, from historical evidence, Donglang (Doklam) has always been traditional pasture area for the border inhabitants of Yadong, a county in its autonomous region of Tibet, and that China had exercised good administration over the area.[60][61] It also says that before the 1960s, if the border inhabitants of Bhutan wanted to herd in Doklam, they needed the consent of the Chinese side and had to pay the grass tax to China.[60]Vorlage:Better sourceVorlage:Full citation needed

Bhutanese reactions

After issuing a press statement on 29 June 2017, the Bhutanese government and media maintained a studious silence.[62] The Bhutanese clarified that the land on which China was building a road was "Bhutanese territory" that was being claimed by China, and it is part of the ongoing border negotiations.[63] It also defended the policy of silence followed by the Bhutanese government, saying "Bhutan does not want India and China to go to war, and it is avoiding doing anything that can heat up an already heated situation."[64] However, ENODO Global, having done a study of social media interactions in Bhutan, recommended that the government should "proactively engage" with citizens and avoid a disconnect between leaders and populations. ENODO found considerable anxiety among the populace regarding the risk of war between India and China, and the possibility of annexation by China similar to that of Tibet in 1951. It found a strengthening of Bhutanese resolve, identity and nationalism, not wanting to be "pushovers".[65][66]

The New York Times said that it encountered more people concerned about India's actions than China's. It found expressions of sovereignty and concern that an escalation of the border conflict would hurt trade and diplomatic relations with China.[62] ENODO did not corroborate these observations. Rather it said that hundreds of Twitter hashtags were created to rally support for India and that there was a significant blowback over the Xinhua television programme titled "7 sins" that castigated India.[66] Scholar Rudra Chaudhuri, having toured the country, noted that Doklam is not as important an issue for the Bhutanese as it might have been ten years ago. Rather the Bhutanese view a border settlement with China as the top priority for the country. While he noticed terms such as "pro-Chinese" and "anti-Indian" often used, he said that what they meant was not well-understood.[34]

Disengagement

On 28 August 2017, it was announced that India and China had mutually agreed to a speedy disengagement on the Doklam plateau bringing an end to the military face-off that lasted for close to three months.[67] The Chinese foreign ministry sidestepped the question of whether China would continue the road construction.[68][69][70]

See also

Notes

References

Bibliography

- Scholarly sources

- Bajpai, G. S. (1999) China's Shadow Over Sikkim: The Politics of Intimidation[1], Lancer Publishers, ISBN 978-1-897829-52-3

- India, China and Sub-regional Connectivities in South Asia[2], SAGE Publications, 2015, ISBN 978-93-5150-326-2

- Fravel, M. Taylor (2008) Strong Borders, Secure Nation: Cooperation and Conflict in China's Territorial Disputes[3], Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-1-4008-2887-6

- Garver, John W. (2011) Protracted Contest: Sino-Indian Rivalry in the Twentieth Century[4], University of Washington Press, ISBN 978-0-295-80120-9

- Harris, George L. (1977) Area Handbook for Nepal, Bhutan and Sikkim[5], second edition, U.S. Government Printing Office

- Joshi, Manoj (2017) Doklam: To start at the very beginning[6], Observer Research Foundation

- Pranav Kumar, Alka Acharya, Jabin T. Jacob: Sino-Bhutanese Relations. In: China Report. 46, Nr. 3, 2011, ISSN 0009-4455, S. 243–252. doi:10.1177/000944551104600306.

- Mathou, Thierry (2004), “Bhutan–China Relations: Towards a New step in Himalayan Politics”, in The Spider and The Piglet: Proceedings of the First International Seminar on Bhutanese Studies, Thimpu: The Centre for Bhutan Studies

- Mullard, Saul (2011) Opening the Hidden Land: State Formation and the Construction of Sikkimese History[7], BRILL, ISBN 978-90-04-20895-7

- Penjore, Dorji (2004), “Security of Bhutan: walking between the giants”, in Journal of Bhutan Studies[8]

- Phuntsho, Karma (2013) The History of Bhutan[9], Random House India, ISBN 978-81-8400-411-3

- Prescott, John Robert Victor (1975) Map of Mainland Asia by Treaty[10], Melbourne University Press, ISBN 978-0-522-84083-4

- Nepal – Strategy for Survival[11], University of California Press, 1971, ISBN 978-0-520-01643-9

- Shakabpa, Tsepon Wangchuk Deden (1984) Tibet: A Political History[12], New York: Potala Publications, ISBN 978-0-9611474-0-2

- Singh, Mandip (2013) Critical Assessment of China's Vulnerabilities in Tibet[13], Institute for Defence Studies & Analyses, ISBN 978-93-82169-10-9

- Smith, Paul J. (2015), “Bhutan–China Border Disputes and Their Geopolitical Implications”, in Beijing's Power and China's Borders: Twenty Neighbors in Asia, M.E. Sharpe, ISBN 978-0-7656-2766-7, pages 23–36

- Van Praagh, David (2003) Greater Game: India's Race with Destiny and China[14], McGill-Queen's Press - MQUP, ISBN 978-0-7735-7130-3, pages 349–

- Walcott, Susan M. (2010), “Bordering the Eastern Himalaya: Boundaries, Passes, Power Contestations”, in Geopolitics[15], volume 15, DOI:, pages 62–81

- Primary sources

- China Foreign Ministry (2 August 2017) The Facts and China's Position Concerning the Indian Border Troops' Crossing of the China-India Boundary in the Sikkim Sector into the Chinese Territory (2017-08-02)[16], Government of China

- India. Ministry of External Affairs (1966) Notes, Memoranda and Letters Exchanged Between the Governments of India and China, January 1965–February 1966, White Paper No. XII[17]

- India. Ministry of External Affairs (1967) Notes, Memoranda and Letters Exchanged Between the Governments of India and China, February 1966–February 1967, White Paper No. XIII[18]

- India. Ministry of External Affairs (1967) Notes, Memoranda and Letters Exchanged Between the Governments of India and China, February 1967–April 1968, White Paper No. XIV[19]

External links

- Doklam area marked on OpenStreetMap

- Convention Between Great Britain and China relating to Sikkim & Tibet

- Neville Maxwell, THIS IS INDIA’S CHINA WAR, ROUND TWO, 14 July 2017

- Manoj Joshi, India and China after the Doklam Standoff (video), Hudson Institute, 16 November 2017

[[Category:Bhutan–China relations]] [[Category:Bhutan–India relations]] [[Category:Bhutan–China border]] [[Category:China–India relations]] [[Category:Disputed territories in Asia]] [[Category:Territorial disputes of China]]

- ↑ Ramakrushna Pradhan, Doklam Standoff: Beyond Border Dispute, Mainstream Weekly, 29 July 2017.

- ↑ Doklam standoff: China sends a warning to India over border dispute. In: Los Angeles Times, 24 July 2017. Archiviert vom Original am 25 July 2017.

- ↑ Liu Lin (27 July 2017), “India-China Doklam Standoff: A Chinese Perspective”, in The Diplomat[20]

- ↑ a b c d e Ankit Panda (13 July 2017), “The Political Geography of the India-China Crisis at Doklam”, in The Diplomat[21]

- ↑ a b Banyan (27 July 2017), “A Himalayan spat between China and India evokes memories of war”, in The Economist[22]

- ↑ a b Translation of the Proceedings and Resolutions of the 82nd Session of the National Assembly Of Bhutan. June–August 2004. Archiviert vom Original am 7 October 2015. Abgerufen im 20 July 2017.

- ↑ “People say in Doklam, India is better placed. Why do we think Chinese could only act here? says Shyam Saran”, in The Indian Express[23], 12 August 2017

- ↑ Press Release – Ministry of Foreign Affairs. In: www.mfa.gov.bt . 29 June 2017. Archiviert vom Original am 30 June 2017.

- ↑ Imperial Gazetteer of India: Provincial Series[24], Usha, 1984

- ↑ “What's behind the India-China border stand-off?”, in BBC News[25], 5 July 2017

- ↑ a b c Lt Gen H. S. Panag (8 July 2017), “India-China standoff: What is happening in the Chumbi Valley?”, in Newslaundry[26]

- ↑ Vorlage:Harvp; Vorlage:Harvp; Vorlage:Harvp; Vorlage:Harvp

- ↑ Vorlage:Harvp; Vorlage:Harvp; Aadil Brar (12 August 2017), “The Hidden History Behind the Doklam Standoff: Superhighways of Tibetan Trade”, in The Diplomat[27]

- ↑ Geography of a Himalayan Kingdom: Bhutan[28], Concept Publishing Company, 2001, ISBN 978-81-7022-887-5

- ↑ Easton, John (1997) An Unfrequented Highway Through Sikkim and Tibet to Chumolaori[29], Asian Educational Services, ISBN 978-81-206-1268-6

- ↑ Ajai Shukla (4 July 2017), “The Sikkim patrol Broadsword”, in Business Standard[30]

- ↑ “'Bhutan Raised Doklam at All Boundary Negotiations with China' (Interview of Amar Nath Ram)”, in The Wire[31], 21 August 2017

- ↑ Bhardwaj, Dolly (2016), “Factors which influence Foreign Policy of Bhutan”, in Polish Journal of Political Science, volume 2, issue 2

- ↑ Brassard, Caroline (2013), “Bhutan: Cautiously Cultivated Positive Perception”, in A Resurgent China: South Asian Perspectives, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-317-90785-5, archived from [ the original] on 27 August 2017, page 76

- ↑ a b Sir Clements Robert Markham: Narratives of the Mission of George Bogle to Tibet and of the Journey of Thomas Manning to Lhasa. Trübner and Co., 1876.

- ↑ Banerji, Arun Kumar (2007), “Borders”, in Jayanta Kumar Ray, editor, Aspects of India's International Relations, 1700 to 2000: South Asia and the World, Pearson Education India, ISBN 978-81-317-0834-7, page 196

- ↑ Vorlage:Harvp; Vorlage:Harvp; Vorlage:Harvp; Vorlage:Harvp

- ↑ Kharat, Rajesh (2009), “Indo-Bhutan relations: Strategic perspectives”, in K. Warikoo, editor, Himalayan Frontiers of India: Historical, Geo-Political and Strategic Perspectives, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-134-03294-5, archived from [ the original] on 27 August 2017, page 139

- ↑ Manoj Joshi (20 July 2017), “Doklam, Gipmochi, Gyemochen: It's Hard Making Cartographic Sense of a Geopolitical Quagmire”, in The Wire[32]

- ↑ Govinda Rizal (27 July 2017), “While the big and the small dragons tryst in Dok-la, the elephant trumpets loud”, in Bhutan News Service[33]

- ↑ a b c d Sandeep Bharadwaj (9 August 2017), “Doklam may bring Bhutan closer to India”, in livemint[34]

- ↑ a b c d e Benedictus, Brian (2 August 2014), “Bhutan and the Great Power Tussle”, in The Diplomat[35], archived from the original on 22 December 2015

- ↑ Desai, B. K. (1959) India, Tibet and China[36], Bombay: Democratic Research Service, archived from the original on 27 August 2017

- ↑ “Delhi Diary, 14 August 1959”, in The Eastern Economist; a Weekly Review of Indian and International Economic Affairs, Volume 33, Issues 1–13, 1959, archived from [ the original] on 27 August 2017

- ↑ George N. Patterson ((Please provide a date)) China's Rape of Tibet[37], George N. Patterson web site

- ↑ Claude Arpi (17 August 2017), “Middle Kingdom's Dream to Become a 'Big Insect'”, in The Pioneer[38]

- ↑ People's China and International Law, Volume 1: A Documentary Study[39], Princeton University Press, 2017, ISBN 978-1-4008-8760-6

- ↑ Jha, Tilak (2013) China and its Peripheries: Limited Objectives in Bhutan[40], New Delhi: Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies, Issue Brief #233, archived from the original on 27 January 2017

- ↑ a b Rudra Chaudhuri, Looking for Godot, The Indian Express, 3 September 2017.

- ↑ Taylor & Francis Group (2004) Europa World Year[41], Taylor & Francis, ISBN 978-1-85743-254-1, pages 794

- ↑ Vorlage:Harvp; Vorlage:Harvp; Vorlage:Harvp; Vorlage:Harvp; Vorlage:Harvp

- ↑ Vorlage:Cite magazine

- ↑ a b Proceedings and Resolutions of the 4th Session of the National Assembly[42], National Assembly of Bhutan, 2009

- ↑ Govinda Rizal (1 January 2013), “Bhutan-China Border Mismatch”, in Bhutan News Service[43]

- ↑ Allison Fedirka (5 August 2017), “China and India may be on a path to war”, in Business Insider UK[44]

- ↑ Vorlage:Harvp: "According to the Convention, the Dong Lang area, which is located on the Chinese side of the boundary, is indisputably Chinese territory. For long, China’s border troops have been patrolling the area and Chinese herdsmen grazing livestock there."

- ↑ a b Anglo-Chinese Treaty of 1890. British Foreign Office, London 1894, S. 1. Archiviert vom Original am 9 July 2017 (Abgerufen am 19 July 2017).

- ↑ Alex McKay: History of Tibet. Routledge Curzon, London 2003, ISBN 9780415308427, S. 142.

- ↑ Srinath Raghavan (7 August 2017), “China is wrong on Sikkim-Tibet boundary”, in livemint[45]

- ↑ Staff: Indian bunker in Sikkim removed by China: Sources. In: The Times of India, 28 June 2017.

- ↑ Shaurya Karanbir Gurung (3 July 2017), “Behind China's Sikkim aggression, a plan to isolate Northeast from rest of India”, in Economic Times[46]

- ↑ Ankit Panda (18 July 2017), “What's Driving the India-China Standoff at Doklam?”, in The Diplomat[47]

- ↑ South Asia news, business and economy from India and Pakistan. In: Asia Times Online. Abgerufen im 19 July 2017.

- ↑ The Tribune, Chandigarh, India - Editorial. In: www.tribuneindia.com . Archiviert vom Original am 20 April 2017. Abgerufen im 19 July 2017.

- ↑ Sikkim standoff: Beijing should realise Bhutan is as important to India as North Korea is to ChinaBitte entweder wayback- oder webciteID- oder archive-is- oder archiv-url-Parameter angeben, First PostBitte entweder wayback- oder webciteID- oder archive-is- oder archiv-url-Parameter angeben, 30 June 2017.

- ↑ Vishnu Som: At Heart Of India-China Standoff, A Road Being Built: 10 Points. In: NDTV, 29 June 2017.

- ↑ Bhutan protests against China's road construction. In: The Straits Times. 30 June 2017. Archiviert vom Original am 29 July 2017. Abgerufen am 7. Juli 2017.

- ↑ Bhutan issues scathing statement against China, claims Beijing violated border agreements of 1988, 1998. In: Firstpost. 30 June 2017. Archiviert vom Original am 2 July 2017. Abgerufen am 30. Juni 2017.

- ↑ EXCLUSIVE: China releases new map showing territorial claims at stand-off site. Archiviert vom Original am 4 July 2017. Abgerufen im 6 July 2017.

- ↑ Nehru Accepted 1890 Treaty; India Using Bhutan to Cover up Entry: China. Archiviert vom Original am 30 July 2017. Abgerufen im 6 July 2017.

- ↑ PTI: No dispute with Bhutan in Doklam: China. In: The Economic Times . 5 July 2017. Archiviert vom Original am 29 July 2017. Abgerufen im 6 July 2017.

- ↑ Bhutan Denies Ceded Claim Over Doklam. 11 August 2017. Archiviert vom Original am 13 August 2017. Abgerufen im 13 August 2017.

- ↑ Don’t interfere in Bhutan’s dispute, China warns India in statement on DoklamBitte entweder wayback- oder webciteID- oder archive-is- oder archiv-url-Parameter angeben, livemint, 2 August 2017.

- ↑ Bhutan acknowledges that Doklam belongs to China: Chinese official. 8 August 2017.

- ↑ a b Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Lu Kang's Regular Press Conference on June 30, 2017. In: www.fmprc.gov.cn . Archiviert vom Original am 4 July 2017.

- ↑ Sikkim standoff: China rejects Bhutan's claim, says Doklam has historically been their territory (en-US). In: Firstpost, 30. Juni 2017. Archiviert vom Original am 16 August 2017.

- ↑ a b Steven Lee Myers: Squeezed by an India-China Standoff, Bhutan Holds Its Breath. In: New York Times, 15 August 2017.

- ↑ Tenzing Lamsang, Understanding the Doklam border issue, The Bhutanese, 1 July 2017.

- ↑ Tenzing Lamsang, The Third Leg of Doklam, The Bhutanese, 5 August 2017.

- ↑ Akhilesh Pillalamarri & Aswin Subanthore, What Do the Bhutanese People Think About Doklam?, The Diplomat, 14 August 2017.

- ↑ a b Conflict Resolution: A Population-Centric Approach to Manage Regional Instability – Real-Time Social Media Analysis of the Standoff in Bhutan, ENODO GLobal, August 2017.

- ↑ Doklam standoff ends; India, China agree to disengage. 28. August 2017.

- ↑ China sidesteps issue of road construction in Doklam, The Hindu, 29 August 2017.

- ↑ “Will China resme building roads in Doklam”, in Rediff News[48], 29 August 2017

- ↑ Doklam: China claims India has withdrawn troops in Doklam, silent on plans to build road. In: The Economic Times . 12 July 2018.

Referenzfehler: <ref>-Tags existieren für die Gruppe lower-alpha, jedoch wurde kein dazugehöriges <references group="lower-alpha" />-Tag gefunden.