Benutzer:Shi Annan/Blue Creek

Wenn du dies liest:

|

Wenn du diesen Artikel überarbeitest:

|

Blue Creek ist eine bedeutende archäologische Stätte im Nordwesten von Belize in Mittelamerika.[1] Sie ist nach dem gleichnamigen Flusssystem des Blue Creek (Rio Azul) benannt. Die Stätte steht in Verbindung mit der archäologischen Stätte Río Azul im Departamento Petén, Guatemala, nur wenige Kilometer Luftlinie südwestlich.

Geographie

Die Stätte liegt am nördlichen Rand der Klippen des Bravo Escarpment im Nordwesten von Belize[2], nahe der heutigen Grenze zwischen Belize und Mexiko und erstrecken sich nach Südwesten über die Grenze zwischen Guatemala und Mexico.[3]

Sie ist mittlerweile als eine von mehreren archäologischen Stätten in der näheren Umgebung identifiziert[4] und liegt in einer Region von drei Flüssen, wo Rio Azul, Booth’s River und Rio Bravo zusammenfließen und gemeinsam den Rio Hondo bilden.[5] Die Nordgreze der Stätte liegt an einem Canyon, mit Wassertiefen von mehr als 100 m, wo der Rio Hondo in die Klippen hineinstürzt.[2]

Blue Creek verbindet das Karibische Meer mit den Küstensiedlungen in Belize über den Rio Hondo[2] und ist geteilt in zwei Sektionen im Eastern Petén und im Belize Coastal Plain (Küstenebene).[4] Das Petén-Plateau ist ein Kalksteinreiches Gebiet mit Anhöhen, welche durch Flüsse mit den ‘Bajos’, Senken im Ökosystem aus Feuchtgebieten verbunden sind.[6][5] Die Rio Bravo Depression ist ein bedeutendes Beispiel fü die ökologische Vielfalt der Stätte, da sie sowohl Feuchtgebiete, als auch Trockenzonen umfasst.[4]

Während die die flache Umgebung heute weitgehend landwirtschaftlich genutzt wird, ziehen sich die Ruinen in einem noch bewaldeten Streifen entlang des Flusses von Norden zur Grenze zu Guatemala nach Süden.[7]

Archäologie

Zahlreiche Artefakte wurden an der Stelle gefunden und zeigen, dass die Stätte von Blue Creek von mehreren antiken Maya-Gemeinschaften seit der mittleren vorklassischen Periode bis zur spätklassischen Periode der Mesoamerikanischen Chronologie besiedelt war.[1][3] Archäologen kamen erst im 20. Jahrhundert nach Blue Creek, als eine Studie von der Regierung in Auftrag gegeben wurde, und es sind keine offiziellen Forschungen vor 1973 bekannt. Seither wurde das Gebiet jedoch von verschiedenen Teams von Wissenschaftlern und Landwirtschaftsexperten untersucht.[1]

Daten zeigen, dass die Stätte während der 800er Jahre (A.D.) verlassen wurde.[1] 200 Jahre später fand nochmals eine Teilbesiedlung am Ende der klassischen Periode statt.[8][9] Während es viele Theorien zum Fall des Maya-Imperiums gibt, deuten die Funde darauf hin, dass es einen deutlichen Bevölkerungsrückgang und einen langsamen Verfall der Infrastruktur gab.[8] Eine Fallstudie von 2016 zur Rolle der Könige in Blue Creek deutet daraufhin, das der Umgang mit bedeutenden Umweltproblemen wie Trockenheit oder Bodenerosion[9] zusammen mit dem Umgang mit Ressourcen ein Faktor beim Zusammenbruch der Gesellschaft gewesen sein könnte.[8] Andere vermuten, dass allgemeine Bodenverschlechterung, der Grund für den Zusammenbruch der Gesellschaft gewesen sien könnte.[6]

Im 21. Jahrhundert wird die Forschung mit Hilfe von Nichtregierungsorganisation und freiwilligen Helfern fortgeführt udie Stätte wird weiterhin dokumentiert, geschützt und konserviert.[10]

Landwirtschaft

Da Blue Creek in einem Gebiet mit zahlreichen ultiple environmental Ökotonen, it has significant variation in types of land and soil, which historically provided the Maya people with constancy in their food production throughout the year.[4] In particular, the fertile soil above the Bravo escarpment where Blue Creek is located, has been commended by modern farmers who have consistently harvested successful dry-farming crops.[1][4] Pollen samples from Laguna Verde, at the Blue Creek site, and their position in the pollen spectrum, have allowed historians to reconstruct past vegetation the environmental conditions of Blue Creek periodically (Morse, 2009).

The Mayan ‘terracing' technique has provided the foundations for contemporary sustainable farming.[6] The primary purpose of the terracing technique is to limit the erosion of soil to provide a solid foundation for planting, as well as maximizing soil moisture,[6] but also utilized the available land in areas with steep slopes that would ordinarily be unsuitable for planting.[6] This technique began in the early classic period at Blue Creek as a response to the occurrence of increased soil erosion evident in the pre-classic period, and utilized check dams and naturally occurring canals.[5] It later developed in the late classic period into dry slope terracing, which may have facilitated Blue Creek’s urban growth.[5] Many of these ancient terraces are still functioning today.[6]

Furthermore archaeological remains uncovered in the upland terrain of Blue Creek, show that the Ancient Maya people used solar observation, water management, and the manipulation of soil fertility to their gain.[5][3] Knowledge about the sun and its place in the solar system was a vital factor in food production for the Maya people.[3] Ethnographic accounts of Maya culture show that Mesoamerican communities deeply ingrained rituals in their agricultural practices.[3] Sacrifices and offerings were made in a ceremony to guarantee rainfall and successful crops.[3] The Quincunx group in the hinterland, just 2.5km behind Blue Creek, is an architectural design consisting of five structures placed in a strategic square, with one construction in the middle.[3] This design facilitated a widely used agricultural ritual used by people to determine cosmological patterns and solstices during the late classic period.[3] Access to the river was a vital asset to engaging in successful agricultural practices.[3]

Architecture and social structure

Most of Blue Creek’s architectural structures followed the edge of the Bravo escarpment, with similar structures to that of nearby regions.[1] Blue Creek’s core area of 20 square kilometers is believed to have been the social hub of the district where historians uncovered the remains of two plaza complexes, a ball court constructed in the early classic period, and two courtyards whose purposes are still debated.[1] The organization of the Blue Creek site was highly intentional and deliberately calculated by the Maya people, to build structures that reflect sacred and cultural significance.[11] The practical design of the area facilitated social communication and provided areas for agricultural, religious, and administrative activities that were engrained heavily in ritualistic ideology.[11] Four periods of architectural transformation have been identified within the terminal pre-classic era, the early classic era, and the late classic era.[11]

At some point during 500 A.D., Blue Creek is believed to have been taken over by a larger neighboring political force.[12] This is evident through the lack of construction and the presence of jade after this period.[12] The other major component of the Blue Creek site is known as the Western Group by historians.[12] Elite residences generally were differentiated by historians from examining their architectural scale and their location with regards to the center of the district as well as essential resources.[12]

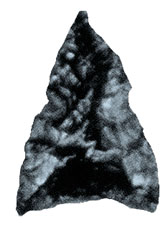

The site divides into two subdivisions that operate in separate functional roles, titled by historians as Plaza A and Plaza B.[1] Archaeologists have found more than 400 residential structures at Blue Creek, indicating the separation evident between the elite and common classes.[13] This social divide was revealed through the excavation of structure 9, now commonly known as “The Temple of the Masks”,[14][1] displaying that the belief in divine kingship was a significant part of the social structure at Blue Creek. The preserved masks were found on the outside of the temple’s façade, and have been dated back to the early classic period, despite being thought initially to have come from the late classic period.[15][1] Pictured to the right is an image of the relief located outside of ‘The Temple of Masks’.[1] This area is believed to be an elite residence where the ‘ajaw’ mask signifies that it was a house for Maya rulers.[12] The term ‘ajaw’ refers to the image of the half abstracted face, which is symbolic of the lord.[12] The bibs underneath each mask indicate its origins from the early classic period.[1] This structure suggests that Blue Creek was an independent community with its own hierarchy and ruling system.[1] Further evidence of religious practices is apparent through a structure located at the back of Plaza B, titled the ‘Temple of the Obsidian Warrior’.[1] This temple was looted like many other structures at Blue Creek,[1] which have provided significant obstacles in the research of archaeologists.

Another excavation revealed an early classic colonnaded building at Blue Creek, which was an unusual architectural form as compared to typical Maya structures, which were composed of thick masonry.[16] Plaza A at the Blue Creek site encompasses six of these traditional masonry structures.[17] The building was thought to be a viewing platform for public activities, as it was elevated and consisted of 8 columns rather than solid walls at both the rear and front end of the structure.[16]

The discovery of a cache (Hoard) vessel inside a small temple as a part of the 1998 field season at Blue Creek, reveals much about the importance of cosmology in Maya religion and creation theory.[17] The Tonina shrine, located inside structure 3, consists of mountain and hearthstone depictions, which are thought to be direct references to concepts surrounding creation as a valued cultural belief.[17] The relationship between the Temple itself and the mountain pictured is believed to be symbolic of Sacred Maya landscapes.[17] The limestone boulder found in structure 3, suggests that this was also a valuable resource kept at Blue Creek.[17]

Economy and trade

Generally, it is now thought that Mayan communities specialized in specific resources and functioned independently and freely, which contrasts the classic ideology where larger hegemonic Maya centers governed production schedules.[18] Blue Creek itself had access to a high amount of exotic goods and was a wealthy community.[13] Many archeologists attribute the success and wealth of Blue Creek, even as a medium-sized center to their strategic location on the Hondo River, and thus to Caribbean coastal communities and economic centers.[12]

Evidence of the riverine trade system between pre-Columbian communities consists of a dock and dam complex found on the Hondo River just above the Blue Creek site. Furthermore, deposits from Blue Creek date back to the pre-classic and classic periods.[2] Cobblestones were used as raw building materials to construct docks and dams to facilitate trade and communication.[2] The contents of these deposits confirm the trading practices that took place between Blue Creek and as far south as Motagua River groups, located in Guatemala.[2] These resources were an essential part of the Maya community as they profoundly influenced the hierarchy present in both socio and economic categories.[19] Archaeological evidence of stone tools from Colha displays that industrial manufacturing was also occurring during the pre-Columbian period and sent to Blue Creek through a communications and commerce network.[2]

Resources

The quality of the soil at Blue Creek as an agricultural base, was a major resource for the site.[13] Conflict in the late classic era is thought by many to be the result of Blue Creek’s increasing population and decreasing agricultural productivity and thus competition for soil as a resource, positioning it in a degree of high importance.[13] Evidence also suggests that resources such as jadeite and nephrite were precious resources at Blue Creek and a significant source of wealth.[8] More than 1,500 jade objects, as well as obsidian blades, metamorphic grinding stones, and sponges from the Caribbean coast, were found at the Blue Creek site.[8] The majority of this jade was located in areas of ritual importance such as structure four, tomb five, and tomb seven.[12] In total, 458 pieces of obsidian were found in structure four, making up 425 blades and 27 cores which were all traced back to El Chayal source.[20] El Chayal is an ancient site located just outside of the modern Guatemala City that had high levels of obsidian deposits, and pre-Columbian communities such as the Maya people, used it as a resource industry.[21] The residue of nine dedicatory cache (Hoard) vessels indicates that sponge and plant remains from the Caribbean coast were valued resources at Blue Creek, in religious and ritual practices.[22] These caches were dedicated to the Gods.[22] Commonly, they consisted of two ceramic bowls, with the second inverted on top of the first to create a spherical structure, with precious materials such as jade, obsidian, shells, and coral placed inside.[22]

Einzelnachweise

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Thomas H. Guderjan: 2004 Public Architecture, Ritual, and Temporal Dynamics at the Maya Center of Blue Creek, Belize. In: Ancient Mesoamerica. journals.cambridge.org vol. 15, 2 2004: S. 235–250. doi=10.1017/S0956536104040167 ISSN 0956-5361

- ↑ a b c d e f g Thomas H. Guderjan: Public Architecture, Ritual, and Temporal Dynamics at the Maya Center of Blue Creek, Belize. In: Ancient Mesoamerica. 15, 2. 2004: 235–250. doi:10.1017/S0956536104040167. ISSN 0956-5361

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Gregory Zaro, Jon C. Lohse: Agricultural Rhythms and Rituals: Ancient Maya Solar Observation in Hinterland Blue Creek, Northwestern Belize. In: Latin American Antiquity. 2005, vol. 16, 1: S. 81–98. doi=10.2307/30042487 jstor=30042487 ISSN 1045-6635.

- ↑ a b c d e T. H. Guderjan, J. Baker, R.J. Lichtenstein: Heterarchy, political economy, and the ancient Maya: The three rivers region of the east-central Yucatˆn Peninsula. University of Arizona Press, Tucson, Arizona: S. 77–91.

- ↑ a b c d e N. Dunning, V. Scarborough, J.F. Valdez, S. Luzzadder-Beach, T. Beach, J.G. Jones: Temple mountains, sacred lakes, and fertile fields: ancient Maya landscapes in northwestern Belize. In: Antiquity. vol. 73, 281, 1999: S. 650–660. doi=10.1017/S0003598X0006525X

- ↑ a b c d e f Timothy Beach, Sheryl Luzzadder-Beach, Nicholas Dunning, Jon Hageman, Jon Lohse: Upland Agriculture in the Maya Lowlands: Ancient Maya Soil Conservation in Northwestern Belize. In: Geographical Review. vol. 92, 3. 2002: S. 372–397. doi=10.1111/j.1931-0846.2002.tb00149.x

- ↑ Blue Creek bei GeoNames, geonames.org. Abgerufen am 6. Juli 2021.

- ↑ a b c d e Thomas H. Guderjan, C. Colleen Hanratty: Events and Processes Leading to the Abandonment of the Maya City of Blue Creek, Belize. In: Gyles Iannone, Brett A. Houk, Sonja A. Schwake (hgg.): Ritual, Violence, and the Fall of the Classic Maya Kings. University Press of Florida 2016-04-12: S. 223–242. doi=10.5744/florida/9780813062754.003.0010 ISBN 978-0-8130-6275-4

- ↑ a b M. L. Morse: Pollen from Laguna Verde, Blue Creek, Belize: Implications for paleoecology, paleoethnobotany, agriculture, and human settlement. Texas A&M University 2009.

- ↑ [www.mayaresearchprogram.org/styled-4/Excavate%20a%20Maya%20city.html Maya Research Program]: Blue Creek Archaeological Project: Field School. mayaresearchprogram.org 2020.

- ↑ a b c Driver, W. D., & Kosakowsky, L. J. (2013). Transforming Identities and Shifting Goods: Tracking Sociopolitical Change through the Monumental Architecture and Ceramic Assemblages at Blue Creek In J. C. Lohse (Ed.), Classic Maya Political Ecology: Resource Management, Class Histories, and Political Change in Northwestern Belize (pp. 69-89) Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Guderjan, T. H., Lichenstein, R. J., Hanratty, C.C. (2010). Elite Residences at Blue Creek Belize In J. J. Christie (Ed.), Maya Palaces and Elite Residences: An Interdisciplinary Approach (pp. 20-24). Austin: University of Texas Press.

- ↑ a b c d Guderjan, T. H. (2007). Agriculture as Blue Creek’s economic base. In The nature of an ancient Maya city: Resources, interaction, and power at Blue Creek, Belize (1st ed., pp. 91-101) Tuscaloosa, Alabama: University of Alabama Press.

- ↑ Haines, Helen R. (1995) Summary of Excavations at the Temple of theMasks. In Archaeological Research at Blue Creek, Belize: Progress Report of the Third (1994) Field Season, edited by Thomas H. Guderjan and W. David Driver, pp. 73–98. Maya Research Program, St. Mary’s University, San Antonio, TX.

- ↑ Grube, Nikolai, Thomas H. Guderjan, and Helen R. Haines. (1995). Late Classic Architecture and Iconography at the Blue Creek Ruin, Belize. Mexicon 17(3):51– 66.

- ↑ a b Driver|first=W. David|date=2002: An Early Classic Colonnaded Building at the Maya Site of Blue Creek, Belize. In: Latin American Antiquity. vol. 13, 1: S. 63–84. (doi=10.2307/971741 jstor=971741) ISSN 1045-6635.

- ↑ a b c d e Driver|first1=W. David|last2=Wanyerka|first2=Phil|date=2002|title=Creation Symbolism in the Architecture and Ritual at Structure 3, Blue Creek, Belize|journal=Mexicon|volume=24|issue=1|pages=6–8|jstor=23759898) ISSN 0720-5988

- ↑ Vernon L. Scarborough, Fred Valdez: An Alternative Order: The Dualistic Economies of the Ancient Maya. In: Latin American Antiquity. 20, Nr. 1, 2009, ISSN 1045-6635, S. 207–227. doi:10.1017/S1045663500002583.

- ↑ Barrett, J. (2004). Constructing hierarchy through entitlement: inequality in lithic resource access among the ancient Maya of Blue Creek, Belize. Ph. D. Dissertation, Department of Anthropology, Texas A & M University, Texas.

- ↑ Haines, H. R. (2000). Intra-site obsidian distribution and consumption patterns in Northern Belize and the North-Eastern Peten (Doctoral dissertation, University College London (University of London).

- ↑ Coe, M., & Flannery, K. (1964). The Pre-Columbian Obsidian Industry of El Chayal, Guatemala. American Antiquity, 30(1), 43-49. doi:10.2307/277629

- ↑ a b c Steven R Bozarth, Thomas H Guderjan: Biosilicate analysis of residue in Maya dedicatory cache (Hoard) vessels from Blue Creek, Belize. In: Journal of Archaeological Science. 31, Nr. 2, 1. Februar 2004, ISSN 0305-4403, S. 205–215. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2003.08.002.

Koordinaten: 17° 52′ 4,8″ N, 88° 53′ 36,4″ W [[Category:Rivers of Belize]] [[Category:Belize–Mexico border]]