Benutzer:Jonathan Scholbach/Evolution der geschlechtlichen Fortpflanzung

Die Evolution der geschlechtlichen Fortpflanzung (Evolution der sexuellen Reproduktion) wird gegenwärtig von verschiedenenen konkurrierenden wissenschaftlichen Hypothesen beschrieben. Alle sich sexuell fortpflanzenden eukaryotischen Organismen stammen von einem gemeinsamem Vorfahren (common ancestor) ab, der eine einzellige eukaryotische Spezies war.[1][2][3] Viele Protisten pflanzen sich geschlechtlich fort, ebenso wie mehrzellige Pflanzen, Tiere und Pilze. Es gibt einige wenige Spezies, die diese Eigenschaft nachträglich wieder verloren haben, wie etwa die Bdelloidea und einige parthenokarpe Pflanzen. Die Evolution der Sexualität beinhaltet zwei verwandte, aber klar getrennte Themen: Einerseits den Ursprung der sexuellen Fortpflanzung, andererseits ihre Aufrechterhaltung. Da die Hypothesen zur Entwicklung der geschlechtlichen Fortpflanzung schwer experimentell überprüfbar sind, konzentriert sich die meiste Arbeit zur Zeit auf den Erhalt der sexuellen Reproduktion.

Es scheint, dass ein Fortpflanzungszyklus evolutionär stabil ist, weil er die biologische [[Fitness] der Nachkommen erhöht, obwohl die Zahl der Nachkommen insgesamt sinkt. (Zweifache Kosten der Sexualität) Damit Sexualität evolutionär vorteilhaft sein kann, muss sie mit einem signifikanten Anstieg der Fitness der Nachkommen einhergehen. Eine der am weitesten akzeptierten Erklärungen für den Vorteil der Sexualität liegt in der Erzeugung genetischer Variation. Eine andere Erklärung basiert auf zwei molekularen Vorteilen. Der erste ist der Vorteil der rekombinanten DNA-Reparatur (während der Meiose weil sich homologe Chromosome zu in dieser Phase paarweise anordnen). Der zweite ist der Vorteil der sogenannten Komplementation (auch bekannt als Heterosis).

For the advantage due to genetic variation, there are three possible reasons this might happen. First, sexual reproduction can combine the effects of two beneficial mutations in the same individual (i.e. sex aids in the spread of advantageous traits). Also, the necessary mutations do not have to have occurred one after another in a single line of descendants.[4]Vorlage:Verify credibility Second, sex acts to bring together currently deleterious mutations to create severely unfit individuals that are then eliminated from the population (i.e. sex aids in the removal of deleterious genes). However in organisms containing only one chromosome, deleterious mutations would be eliminated immediately, and therefore removal of harmful mutations is an unlikely benefit for sexual reproduction. Lastly, sex creates new gene combinations that may be more fit than previously existing ones, or may simply lead to reduced competition among relatives.

For the advantage due to DNA repair, there is an immediate large benefit of removing DNA damage by recombinational DNA repair during meiosis, since this removal allows greater survival of progeny with undamaged DNA. The advantage of complementation to each sexual partner is avoidance of the bad effects of their deleterious recessive genes in progeny by the masking effect of normal dominant genes contributed by the other partner.

The classes of hypotheses based on the creation of variation are further broken down below. It is important to realise that any number of these hypotheses may be true in any given species (they are not mutually exclusive), and that different hypotheses may apply in different species. However, a research framework based on creation of variation has yet to be found that allows one to determine whether the reason for sex is universal for all sexual species, and, if not, which mechanisms are acting in each species.

On the other hand, the maintenance of sex based on DNA repair and complementation applies widely to all sexual species.

Historical perspective

Modern philosophical-scientific thinking on the problem can be traced back to Erasmus Darwin in the 18th century; it also features in Aristotle's writings. The thread was later picked up by August Weismann in 1889, who argued that the purpose of sex was to generate genetic variation, as is detailed in the majority of the explanations below. On the other hand, Charles Darwin concluded that the effects of hybrid vigor (complementation) "is amply sufficient to account for the ... genesis of the two sexes." This is consistent with the repair and complementation hypothesis, given below under "Other explanations."

Several explanations have been suggested by biologists including W. D. Hamilton, Alexey Kondrashov, George C. Williams, Harris Bernstein, Carol Bernstein, Michael M. Cox, Frederic A. Hopf and Richard E. Michod to explain how sexual reproduction is maintained in a vast array of different living organisms.

Two-fold cost of sex

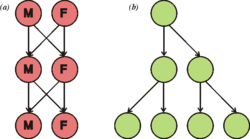

In most multicellular sexual species, the population consists of two sexes, only one of which is capable of bearing young (with the exception of simultaneous hermaphrodites). In an asexual species, each member of the population is capable of bearing young. This implies that an asexual population has an intrinsic capacity to grow more rapidly with each generation. The cost was first described in mathematical terms by John Maynard Smith.[5] He imagined an asexual mutant arising in a sexual population, half of which comprises males that cannot themselves produce offspring. With female-only offspring, the asexual lineage doubles its representation in the population each generation, all else being equal. Technically this is not a problem of sex but a problem of some multicellular sexually reproducing organisms. There are numerous isogamous species which are sexual and do not have the problem of producing individuals which cannot directly replicate themselves.[6] The principal costs of sex is that males and females must search for each other in order to mate, and sexual selection often favours traits that reduce the survival of individuals.[5]

Evidence that the cost is not insurmountable comes from George C. Williams, who noted the existence of species which are capable of both asexual and sexual reproduction. These species time their sexual reproduction with periods of environmental uncertainty, and reproduce asexually when conditions are more favourable. The important point is that these species are observed to reproduce sexually when they could choose not to, implying that there is a selective advantage to sexual reproduction.[7]

It is widely believed that a disadvantage of sexual reproduction is that a sexually reproducing organism will only be able to pass on 50% of its genes to each offspring. This is a consequence of the fact that gametes from sexually reproducing species are haploid.[8] This, however, conflates sex and reproduction which are two separate events. The "two-fold cost of sex" may more accurately be described as the cost of anisogamy. Not all sexual organisms are anisogamous. There are numerous species which are sexual and do not have this problem because they do not produce males. Yeast, for example, are isogamous sexual organisms which have two mating types which fuse and recombine their haploid genomes. Both sexes reproduce during the haploid and diploid stages of their life cycle and have a 100% chance of passing their genes into their offspring.[6]

The two-fold cost of sex may be avoided by species in many ways. Females may eat males after mating, males may be much smaller or rarer, or males may help raise offspring.

Promotion of genetic variation

August Weismann proposed in 1889[9] an explanation for the evolution of sex, where the advantage of sex is the creation of variation among siblings. It was then subsequently explained in genetics terms by Fisher[10] and Muller[11] and has been recently summarised by Burt in 2000.[12]

George C. Williams gave an example based around the elm tree. In the forest of this example, empty patches between trees can support one individual each. When a patch becomes available because of the death of a tree, other trees' seeds will compete to fill the patch. Since the chance of a seed's success in occupying the patch depends upon its genotype, and a parent cannot anticipate which genotype is most successful, each parent will send many seeds, creating competition between siblings. Natural selection therefore favours parents which can produce a variety of offspring (see lottery principle).

A similar hypothesis is named the tangled bank hypothesis after a passage in Charles Darwin's The Origin of Species:

- "It is interesting to contemplate an entangled bank, clothed with many plants of many kinds, with birds singing on the bushes, with various insects flitting about, and with worms crawling through the damp earth, and to reflect that these elaborately constructed forms, so different from each other, and dependent on each other in so complex a manner, have all been produced by laws acting around us."

The hypothesis, proposed by Michael Ghiselin in his 1974 book, The Economy of Nature and the Evolution of Sex, suggests that a diverse set of siblings may be able to extract more food from its environment than a clone, because each sibling uses a slightly different niche. One of the main proponents of this hypothesis is Graham Bell of McGill University. The hypothesis has been criticised for failing to explain how asexual species developed sexes. In his book, Evolution and Human Behavior (MIT Press, 2000), John Cartwright comments:

- "Although once popular, the tangled bank hypothesis now seems to face many problems, and former adherents are falling away. The theory would predict a greater interest in sex among animals that produce lots of small offspring that compete with each other. In fact, sex is invariably associated with organisms that produce a few large offspring, whereas organisms producing small offspring frequently engage in parthenogenesis [asexual reproduction]. In addition, the evidence from fossils suggests that species go for vast periods of [geologic] time without changing much."

Spread of advantageous traits

Novel genotypes

Sex could be a method by which novel genotypes are created. Since sex combines genes from two individuals, sexually reproducing populations can more easily combine advantageous genes than can asexual populations. If, in a sexual population, two different advantageous alleles arise at different loci on a chromosome in different members of the population, a chromosome containing the two advantageous alleles can be produced within a few generations by recombination. However, should the same two alleles arise in different members of an asexual population, the only way that one chromosome can develop the other allele is to independently gain the same mutation, which would take much longer.

Ronald Fisher also suggested that sex might facilitate the spread of advantageous genes by allowing them to escape their genetic surroundings, if they should arise on a chromosome with deleterious genes.

Supporters of these theories respond to the balance argument that the individuals produced by sexual and asexual reproduction may differ in other respects too – which may influence the persistence of sexuality. For example, in water fleas of the genus Cladocera, sexual offspring form eggs which are better able to survive the winter.

Increased resistance to parasites

One of the most widely accepted theories to explain the persistence of sex is that it is maintained to assist sexual individuals in resisting parasites, also known as the Red Queen's Hypothesis.[8][13][14]

When an environment changes, previously neutral or deleterious alleles can become favourable. If the environment changed sufficiently rapidly (i.e. between generations), these changes in the environment can make sex advantageous for the individual. Such rapid changes in environment are caused by the co-evolution between hosts and parasites.

Imagine, for example that there is one gene in parasites with two alleles p and P conferring two types of parasitic ability, and one gene in hosts with two alleles h and H, conferring two types of parasite resistance, such that parasites with allele p can attach themselves to hosts with the allele h, and P to H. Such a situation will lead to cyclic changes in allele frequency - as p increases in frequency, h will be disfavoured.

In reality, there will be several genes involved in the relationship between hosts and parasites. In an asexual population of hosts, offspring will only have the different parasitic resistance if a mutation arises. In a sexual population of hosts, however, offspring will have a new combination of parasitic resistance alleles.

In other words, like Lewis Carroll's Red Queen, sexual hosts are continually adapting in order to stay ahead of their parasites.

Evidence for this explanation for the evolution of sex is provided by comparison of the rate of molecular evolution of genes for kinases and immunoglobulins in the immune system with genes coding other proteins. The genes coding for immune system proteins evolve considerably faster.[15][16]

Further evidence for the Red Queen hypothesis were provided by observing long‐term dynamics and parasite coevolution in a "mixed" (sexual and asexual) population of snails (Potamopyrgus antipodarum). The number of sexuals, the number asexuals, and the rates of parasite infection for both were monitored. It was found that clones that were plentiful at the beginning of the study became more susceptible to parasites over time. As parasite infections increased, the once plentiful clones dwindled dramatically in number. Some clonal types disappeared entirely. Meanwhile, sexual snail populations remained much more stable over time.[17][18]

In 2011, researchers used the microscopic roundworm Caenorhabditis elegans as a host and the pathogenic bacteria Serratia marcescens to generate a host-parasite coevolutionary system in a controlled environment, allowing them to conduct more than 70 evolution experiments testing the Red Queen Hypothesis. They genetically manipulated the mating system of C. elegans, causing populations to mate either sexually, by self-fertilization, or a mixture of both within the same population. Then they exposed those populations to the S. marcescens parasite. It was found that the self-fertilizing populations of C. elegans were rapidly driven extinct by the coevolving parasites while sex allowed populations to keep pace with their parasites, a result consistent with the Red Queen Hypothesis.[19][20]

Critics of the Red Queen hypothesis question whether the constantly changing environment of hosts and parasites is sufficiently common to explain the evolution of sex. In particular, Otto and Nuismer [21] presented results showing that species interactions (e.g. host vs parasite interactions) typically select against sex. They concluded that, although the Red Queen hypothesis favors sex under certain circumstances, it alone does not account for the ubiquity of sex. Otto and Gerstein [22] further stated that “it seems doubtful to us that strong selection per gene is sufficiently commonplace for the Red Queen hypothesis to explain the ubiquity of sex.” Parker [23] reviewed numerous genetic studies on plant disease resistance and failed to uncover a single example consistent with the assumptions of the Red Queen hypothesis.

Deleterious mutation clearance

Mutations can have many different effects upon an organism. It is generally believed that the majority of non-neutral mutations are deleterious, which means that they will cause a decrease in the organism's overall fitness.[24] If a mutation has a deleterious effect, it will then usually be removed from the population by the process of natural selection. Sexual reproduction is believed to be more efficient than asexual reproduction in removing those mutations from the genome.[25]

There are two main hypotheses which explain how sex may act to remove deleterious genes from the genome.

Maintenance of mutation-free individuals

In a finite asexual population under the pressure of deleterious mutations, the random loss of individuals without such mutations is inevitable. This is known as Muller's ratchet. In a sexual population, however, mutation-free genotypes can be restored by recombination of genotypes containing deleterious mutations.

This comparison will only work for a small population - in a large population, random loss of the most fit genotype becomes unlikely even in an asexual population.

Removal of deleterious genes

This hypothesis was proposed by Alexey Kondrashov, and is sometimes known as the deterministic mutation hypothesis.[25] It assumes that the majority of deleterious mutations are only slightly deleterious, and affect the individual such that the introduction of each additional mutation has an increasingly large effect on the fitness of the organism. This relationship between number of mutations and fitness is known as synergistic epistasis.

By way of analogy, think of a car with several minor faults. Each is not sufficient alone to prevent the car from running, but in combination, the faults combine to prevent the car from functioning.

Similarly, an organism may be able to cope with a few defects, but the presence of many mutations could overwhelm its backup mechanisms.

Kondrashov argues that the slightly deleterious nature of mutations means that the population will tend to be composed of individuals with a small number of mutations. Sex will act to recombine these genotypes, creating some individuals with fewer deleterious mutations, and some with more. Because there is a major selective disadvantage to individuals with more mutations, these individuals die out. In essence, sex compartmentalises the deleterious mutations.

There has been much criticism of Kondrashov's theory, since it relies on two key restrictive conditions. The first requires that the rate of deleterious mutation should exceed one per genome per generation in order to provide a substantial advantage for sex. While there is some empirical evidence for it (for example in Drosophila[28] and E. coli[29]), there is also strong evidence against it. Thus, for instance, for the sexual species Saccharomyces cerevisiae (yeast) and Neurospora crassa (fungus), the mutation rate per genome per replication are 0.0027 and 0.0030 respectively. For the nematode worm Caenorhabditis elegans, the mutation rate per effective genome per sexual generation is 0.036[30]. Secondly, there should be strong interactions among loci (synergistic epistasis), a mutation-fitness relation for which there is only limited evidence. Conversely, there is also the same amount of evidence that mutations show no epistasis (purely additive model) or antagonistic interactions (each additional mutation has a disproportionally small effect).

Other explanations

Speed of evolution

Ilan Eshel suggested that sex prevents rapid evolution. He suggests that recombination breaks up favourable gene combinations more often than it creates them, and sex is maintained because it ensures selection is longer-term than in asexual populations - so the population is less affected by short-term changes.Vorlage:Citation needed This explanation is not widely accepted, as its assumptions are very restrictive.

It has recently been shown in experiments with Chlamydomonas algae that sex can remove the speed limit on evolution.[31]

DNA repair and complementation

As discussed in the earlier part of this article, sexual reproduction is conventionally explained as an adaptation for producing genetic variation through allelic recombination. As acknowledged above, however, serious problems with this explanation have led many biologists to conclude that the benefit of sex is a major unsolved problem in evolutionary biology.

An alternative "informational" approach to this problem has led to the view that the two fundamental aspects of sex, genetic recombination and outcrossing, are adaptive responses to the two major sources of "noise" in transmitting genetic information. Genetic noise can occur as either physical damage to the genome (e.g. chemically altered bases of DNA or breaks in the chromosome) or replication errors (mutations)[32][33][34] This alternative view is referred to as the repair and complementation hypothesis, to distinguish it from the traditional variation hypothesis.

The repair and complementation hypothesis assumes that genetic recombination is fundamentally a DNA repair process, and that when it occurs during meiosis it is an adaptation for repairing the genomic DNA which is passed on to progeny. Recombinational repair is the only repair process known which can accurately remove double-strand damages in DNA, and such damages are both common in nature and ordinarily lethal if not repaired. Recombinational repair is prevalent from the simplest viruses to the most complex multicellular eukaryotes. It is effective against many different types of genomic damage, and in particular is highly efficient at overcoming double-strand damages. Studies of the mechanism of meiotic recombination indicate that meiosis is an adaptation for repairing DNA.[35][36] These considerations form the basis for the first part of the repair and complementation hypothesis.

In some lines of descent from the earliest organisms, the diploid stage of the sexual cycle, which was at first transient, became the predominant stage, because it allowed complementation — the masking of deleterious recessive mutations (i.e. hybrid vigor or heterosis). Outcrossing, the second fundamental aspect of sex, is maintained by the advantage of masking mutations and the disadvantage of inbreeding (mating with a close relative) which allows expression of recessive mutations (commonly observed as inbreeding depression). This is in accord with Charles Darwin,[37] who concluded that the adaptive advantage of sex is hybrid vigor; or as he put it, "the offspring of two individuals, especially if their progenitors have been subjected to very different conditions, have a great advantage in height, weight, constitutional vigor and fertility over the self fertilised offspring from either one of the same parents."

However, outcrossing may be abandoned in favor of parthogenesis or selfing (which retain the advantage of meiotic recombinational repair) under conditions in which the costs of mating are very high. For instance, costs of mating are high when individuals are rare in a geographic area, such as when there has been a forest fire and the individuals entering the burned area are the initial ones to arrive. At such times mates are hard to find, and this favors parthenogenic species.

In the view of the repair and complementation hypothesis, the removal of DNA damage by recombinational repair produces a new, less deleterious form of informational noise, allelic recombination, as a by-product. This lesser informational noise generates genetic variation, viewed by some as the major effect of sex, as discussed in the earlier parts of this article.

Origin of sexual reproduction

Vorlage:Expand section Sexual reproduction first appeared by 1200 million years ago in the Proterozoic Eon.[38] All sexually reproducing organisms derive from a common ancestor which was a single celled eukaryotic species.[1] Many protists reproduce sexually, as do the multicellular plants, animals, and fungi. There are a few species which have secondarily lost this feature, such as Bdelloidea and some parthenocarpic plants.

Organisms need to replicate their genetic material in an efficient and reliable manner. The necessity to repair genetic damage is one of the leading theories explaining the origin of sexual reproduction. Diploid individuals can repair a damaged section of their DNA via homologous recombination, since there are two copies of the gene in the cell and one copy is presumed to be undamaged. A mutation in an haploid individual, on the other hand, is more likely to become resident, as the DNA repair machinery has no way of knowing what the original undamaged sequence was.[32] The most primitive form of sex may have been one organism with damaged DNA replicating an undamaged strand from a similar organism in order to repair itself.[39]

Another theory is that sexual reproduction originated from selfish parasitic genetic elements that exchange genetic material (that is: copies of their own genome) for their transmission and propagation. In some organisms, sexual reproduction has been shown to enhance the spread of parasitic genetic elements (e.g.: yeast, filamentous fungi).[40] Bacterial conjugation, a form of genetic exchange that some sources describe as sex, is not a form of reproduction, but rather an example of horizontal gene transfer. However, it does support the selfish genetic element theory, as it is propagated through such a "selfish gene", the F-plasmid.[39] Similarly, it has been proposed that sexual reproduction evolved from ancient haloarchaea through a combination of jumping genes, and swapping plasmids.[41]

A third theory is that sex evolved as a form of cannibalism. One primitive organism ate another one, but rather than completely digesting it, some of the 'eaten' organism's DNA was incorporated into the 'eater' organism.[39]

Sex may also be derived from prokaryotic processes. A comprehensive 'origin of sex as vaccination' theory proposes that eukaryan sex-as-syngamy (fusion sex) arose from prokaryan unilateral sex-as-infection when infected hosts began swapping nuclearised genomes containing coevolved, vertically transmitted symbionts that provided protection against horizontal superinfection by more virulent symbionts. Sex-as-meiosis (fission sex) then evolved as a host strategy to uncouple (and thereby emasculate) the acquired symbiont genomes.[42]

Mechanistic origin of sexual reproduction

Though theories positing benefits that lead to the origin of sex are often problematic, several credible theories on the evolution of the mechanisms of sexual reproduction have been proposed.

Viral eukaryogenesis

The viral eukaryogenesis (VE) theory proposes that eukaryotic cells arose from a combination of a lysogenic virus, an archaeon and a bacterium. This model suggests that the nucleus originated when the lysogenic virus incorporated genetic material from the archaeon and the bacterium and took over the role of information storage for the amalgam. The archaeal host transferred much of its functional genome to the virus during the evolution of cytoplasm but retained the function of gene translation and general metabolism. The bacterium transferred most of its functional genome to the virus as it transitioned into a mitochondrion.[43]

For these transformations to lead to the eukaryotic cell cycle, the VE hypothesis specifies a pox-like virus as the lysogenic virus. A pox-like virus is a likely ancestor because of its fundamental similarities with eukaryotic nuclei. These include a double stranded DNA genome, a linear chromosome with short telomeric repeats, a complex membrane bound capsid, the ability to produce capped mRNA, and the ability to export the capped mRNA across the viral membrane into the cytoplasm. The presence of a lysogenic pox-like virus ancestor explains the development of meiotic division, an essential component of sexual reproduction.[44]

Meiotic division in the VE hypothesis arose because of the evolutionary pressures placed on the lysogenic virus as a result of its inability to enter into the lytic cycle. This selective pressure resulted in the development of processes allowing the viruses to spread horizontally throughout the population. The outcome of this selection was cell-to-cell fusion. (This is distinct from the conjugation methods used by bacterial plasmids under evolutionary pressure, with important consequences.)[43] The possibility of this kind of fusion is supported by the presence of fusion proteins in the envelopes of the pox viruses that allow them to fuse with host membranes. These proteins could have been transferred to the cell membrane during viral reproduction, enabling cell-to-cell fusion between the virus host and an uninfected cell. The theory proposes meiosis originated from the fusion between two cells infected with related but different viruses which recognised each other as uninfected. After the fusion of the two cells, incompatibilities between the two viruses result in a meiotic-like cell division.[44]

The two viruses established in the cell would initiate replication in response to signals from the host cell. A mitosis-like cell cycle would proceed until the viral membranes dissolved, at which point linear chromosomes would be bound together with centromeres. The homologous nature of the two viral centromeres would incite the grouping of both sets into tetrads. It is speculated that this grouping may be the origin of crossing over, characteristic of the first division in modern meiosis. The partitioning apparatus of the mitotic-like cell cycle the cells used to replicate independently would then pull each set of chromosomes to one side of the cell, still bound by centromeres. These centromeres would prevent their replication in subsequent division, resulting in four daughter cells with one copy of one of the two original pox-like viruses. The process resulting from combination of two similar pox viruses within the same host closely mimics meiosis.[44]

Neomuran revolution

An alternative theory, proposed by Thomas Cavalier-Smith, was labeled the Neomuran revolution. The designation "Neomuran revolution" refers to the appearances of the common ancestors of eukaryotes and archaea. Cavalier-Smith proposes that the first neomurans emerged 850 million years ago. Other molecular biologists assume that this group appeared much earlier, but Cavalier-Smith dismisses these claims because they are based on the "theoretically and empirically" unsound model of molecular clocks. Cavalier-Smith's theory of the Neomuran revolution has implications for the evolutionary history of the cellular machinery for recombination and sex. It suggests that this machinery evolved in two distinct bouts separated by a long period of stasis; first the appearance of recombination machinery in a bacterial ancestor which was maintained for 3 Gy,Vorlage:Clarify until the neomuran revolution when the mechanics were adapted to the presence of nucleosomes. The archaeal products of the revolution maintained recombination machinery that was essentially bacterial, whereas the eukaryotic products broke with this bacterial continuity. They introduced cell fusion and ploidy cycles into cell life histories. Cavalier-Smith argues that both bouts of mechanical evolution were motivated by similar selective forces: the need for accurate DNA replication without loss of viability.[45]

See also

- Asexual reproduction

- Biological reproduction

- Epistasis

- Genetic recombination

- Interlocus contest evolution

- Meiosis

- Mutation

- Natural competence

- Sexual dimorphism

- Sexual reproduction

- Koinophilia

References

Further reading

- Graham Bell: The masterpiece of nature: the evolution and genetics of sexuality. University of California Press, Berkeley 1982, ISBN 0-520-04583-1.

- Harris Bernstein, Carol Bernstein: Aging, sex, and DNA repair. Academic Press, Boston 1991, ISBN 0-12-092860-4.

- L.D. Hurst, J.R. Peck: Recent advances in the understanding of the evolution and maintenance of sex. In: Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 11, Nr. 2, 1996, S. 46–52. doi:10.1016/0169-5347(96)81041-X. PMID 21237760.

- Bruce R. Levin, Richard E. Michod: The Evolution of sex: an examination of current ideas. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, Mass 1988, ISBN 0-87893-459-6.

- John Maynard Smith: The evolution of sex. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK 1978, ISBN 0-521-21887-X.

- Richard E. Michod: Eros and evolution: a natural philosophy of sex. Addison-Wesley Pub. Co, Reading, Mass 1995, ISBN 0-201-40754-X.

- Scientists put sex origin mystery to bed, Wild strawberry research provides evidence on when gender emerges, MSNBC. Abgerufen am 25. November 2008.

- Mark Ridley: Evolution. Blackwell Scientific, Oxford 1993, ISBN 0-632-03481-5.

- Mark Ridley: Mendel's demon: gene justice and the complexity of life. Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London 2000, ISBN 0-297-64634-6.

- Matt Ridley: The Red Queen: sex and the evolution of human nature. Penguin Books, New York 1995, ISBN 0-14-024548-0.

- Eörs Szathmáry, John Maynard Smith: The Major Transitions in Evolution. W.H. Freeman Spektrum, Oxford 1995, ISBN 0-7167-4525-9.

- Timothy Taylor: The prehistory of sex: four million years of human sexual culture. Bantam Books, New York 1996, ISBN 0-553-09694-X.

- George Williams: Sex and evolution. Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J 1975, ISBN 0-691-08147-6.

External links

- Why Sex is Good

- An essay summarising the different theories, dating from around 2001

- ↑ a b I Letunic, P Bork: Interactive Tree of Life. 2006. Abgerufen im 23 July 2011.

- ↑ I Letunic, P Bork: Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL): An online tool for phylogenetic tree display and annotation. In: Bioinformatics. 23, Nr. 1, 2007, S. 127–8. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btl529. PMID 17050570.

- ↑ I Letunic, P Bork: Interactive Tree of Life v2: Online annotation and display of phylogenetic trees made easy. In: Nucleic Acids Research. 39, 2011, S. W475–8. doi:10.1093/nar/gkr201. PMID 21470960. PMC 3125724 (freier Volltext).

- ↑ R N Goldstein: 36 Arguments for the Existence of God: A Work of Fiction. Pantheon, 2010, ISBN 978-0-307-37818-7.

- ↑ a b John Maynard Smith The Evolution of Sex 1978.

- ↑ a b Rolf Hoekstra 1987 The Evolution of Sex and its Consequences 1988 Birkhauser. Referenzfehler: Ungültiges

<ref>-Tag. Der Name „Hoekstra“ wurde mehrere Male mit einem unterschiedlichen Inhalt definiert. - ↑ George C. Williams Sex and Evolution 1975, Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-691-08152-2

- ↑ a b Matt Ridley 1995 The Red Queen: Sex and the Evolution of Human Nature 1995 Penguin.

- ↑ Weismann, A. 1889. Essays on heredity and kindred biological subjects. Oxford Univ. Press, Oxford, UK

- ↑ Fisher, R. A. 1930. The genetical theory of natural selection. Clarendon Press, Oxford, UK

- ↑ H. J. Muller: Some genetic aspects of sex. In: Am. Nat.. 66, Nr. 703, 1932, S. 118–138. doi:10.1086/280418.

- ↑ A. Burt: Perspective: sex, recombination, and the efficacy of selection—was Weismann right?. In: Evolution. 54, Nr. 2, 2000, S. 337–351. PMID 10937212.

- ↑ L. Van Valen: A New Evolutionary Law. In: Evolutionary Theory. 1, 1973, S. 1–30.

- ↑ W. D. et al. Hamilton: Sexual reproduction as an adaptation to resist parasites. In: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 87, Nr. 9, 1990, S. 3566–3573. doi:10.1073/pnas.87.9.3566.

- ↑ K. Kuma, N. Iwabe, T. Miyata: Functional constraints against variations on molecules from the tissue-level - slowly evolving brain-specific genes demonstrated by protein-kinase and immunoglobulin supergene families. In: Molecular Biology and Evolution. 12, Nr. 1, 1995, S. 123–130. PMID 7877487.

- ↑ Wolfe KH & Sharp PM. 1993. Mammalian gene evolution - nucleotide-sequence divergence between mouse and rat. Journal of molecular evolution 37 (4): 441-456 OCT 1993

- ↑ Jukka Jokela, Mark Dybdahl, Curtis Lively: The Maintenance of Sex, Clonal Dynamics, and Host-Parasite Coevolution in a Mixed Population of Sexual and Asexual Snails. In: The American Naturalist. 174, Nr. s1, 2009, S. S43. doi:10.1086/599080.

- ↑ Parasites May Have Had Role In Evolution Of Sex. Science Daily. 31 July 2009. Abgerufen im 19 September 2011.

- ↑ Levi T. Morran, Olivia G. Schmidt, Ian A. Gelarden, Raymond C. Parrish II, Curtis M. Lively: Running with the Red Queen: Host-Parasite Coevolution Selects for Biparental Sex. In: Science. 333, Nr. 6039, 2011, S. 216–218. doi:10.1126/science.1206360. PMID 21737739.

- ↑ Sex -- As We Know It -- Works Thanks to Ever-Evolving Host-Parasite Relationships, Biologists Find. Science Daily. 9 July 2011. Abgerufen im 19 September 2011.

- ↑ Otto SP, Nuismer SL. (2004) Species interactions and the evolution of sex. Science 304(5673): 1018-1020. PMID: 15143283

- ↑ Otto SP, Gerstein AC. (2006) Why have sex? The population genetics of sex and recombination. Biochem Soc Trans. 34(Pt 4):519-22. Review. PMID: 16856849

- ↑ Parker MA. (1994) Pathogens and sex in plants. Evolutionary Ecology 8: 560-584.

- ↑ Griffiths et al. 1999. Gene mutations, p197-234, in Modern Genetic Analysis, New York, W.H. Freeman and Company.

- ↑ a b A. S. Kondrashov: Deleterious mutations and the evolution of sexual reproduction. In: Nature. 336, Nr. 6198, 1988, S. 435–440. doi:10.1038/336435a0. PMID 3057385.

- ↑ Ridley M (2004) Evolution, 3rd edition. Blackwell Publishing.

- ↑ Charlesworth B, Charlesworth D (2010) Elements of Evolutionary Genetics. Roberts and Company Publishers.

- ↑ M. C. Whitlock, D. Bourget: Factors affecting the genetic load in Drosophila: synergistic epistasis and correlations among fitness components. In: Evolution. 54, Nr. 5, 2000, S. 1654–1660. PMID 11108592.

- ↑ S. F. Elena, R. E. Lenski: Test of synergistic interactions among deleterious mutations in bacteria. In: Nature. 390, Nr. 6658, 1997, S. 395–398. doi:10.1038/37108. PMID 9389477.

- ↑ Drake JW, Charlesworth B, Charlesworth D, Crow JF. (1998) Rates of spontaneous mutation. Genetics 148(4): 1667-86. Review. PMID: 9560386

- ↑ N. Colegrave: Sex releases the speed limit on evolution. In: Nature. 420, Nr. 6916, 2002, S. 664–666. doi:10.1038/nature01191. PMID 12478292.

- ↑ a b Bernstein H, Byerly HC, Hopf FA, Michod RE: Origin of sex. In: J. Theor. Biol.. 110, Nr. 3, 1984, S. 323–51. doi:10.1016/S0022-5193(84)80178-2. PMID 6209512. Referenzfehler: Ungültiges

<ref>-Tag. Der Name „dna-repair“ wurde mehrere Male mit einem unterschiedlichen Inhalt definiert. - ↑ Bernstein H, Byerly HC, Hopf FA, Michod RE: Genetic damage, mutation, and the evolution of sex. In: Science. 229, Nr. 4719, 1985, S. 1277–81. doi:10.1126/science.3898363. PMID 3898363.

- ↑ Bernstein H, Hopf FA, Michod RE: Advances in Genetics Volume 24. In: Adv. Genet.. 24, 1987, S. 323–70. doi:10.1016/S0065-2660(08)60012-7. PMID 3324702.

- ↑ Cox MM: Historical overview: searching for replication help in all of the rec places. In: Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.. 98, Nr. 15, 2001, S. 8173–80. doi:10.1073/pnas.131004998. PMID 11459950. PMC 37418 (freier Volltext).

- ↑ Bernstein H, Bernstein C and Michod RE (2011). Meiosis as an Evolutionary Adaptation for DNA Repair. DNA Repair Dr. Inna Kruman (Ed.), ISBN: 978-953-307-697-3, InTech. Available online from: http://www.intechopen.com/books/dna-repair/meiosis-as-an-evolutionary-adaptation-for-dna-repair

- ↑ Darwin C. 1889. The effects of cross and self fertilisation in the vegetable kingdom. Chapter XII. General Results pp. 436-463. D. Appleton and Company, New York

- ↑ Nicholas J. Butterfield, "Bangiomorpha pubescens n. gen., n. sp.: implications for the evolution of sex, multicellularity, and the Mesoproterozoic/Neoproterozoic radiation of eukaryotes"

- ↑ a b c Olivia Judson: Dr. Tatiana's sex advice to all creation. Metropolitan Books, New York 2002, ISBN 0-8050-6331-5, S. 233–4.

- ↑ Hickey D: Selfish DNA: a sexually-transmitted nuclear parasite. In: Genetics. 101, Nr. 3–4, 1982, S. 519–31. PMID 6293914. PMC 1201875 (freier Volltext).

- ↑ Shiladitya DasSarma: American Scientist. 95, 2007, S. 224–231.

- ↑ Sterrer W: On the origin of sex as vaccination. In: Journal of Theoretical Biology. 216, Nr. 4, 2002, S. 387–396. doi:10.1006/jtbi.2002.3008. PMID 12151256.

- ↑ a b PJ Bell: Viral eukaryogenesis: was the ancestor of the nucleus a complex DNA virus?. In: J Molec Biol. 53, Nr. 3, 2001, S. 251–6.

- ↑ a b c PJ Bell: Sex and the eukaryotic cell cycle is consistent with a viral ancestry for the eukaryotic nucleus. In: J Theor Biol. 243, Nr. 1, 2006, S. 54–63. doi:10.1016/j.jtbi.2006.05.015. PMID 16846615.

- ↑ Cavalier-Smith, Thomas: Cell evolution and Earth history: stasis and revolution. In: Royal Society of Biol Sci. 361, Nr. 1470, 2006, S. 969–1006. doi:10.1098/rstb.2006.1842. PMID 16754610. PMC 1578732 (freier Volltext).